All blog posts and articles written by Peter WB Phillips, Distinguished Professor of Public Policy, Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy and Founding Director of the Centre for the Study of Science and Innovation Policy, University of Saskatchewan.

11 Ways to Measure Clean Growth

Today the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices published a groundbreaking report, 11 Ways to Measure Clean Growth. The report explores data showing how Canada’s prosperity is tied to progress across a range of climate, economic, and social goals. Our analysis finds that, not only are these goals connected, neglecting any one dimension can actually undermine Canada’s long-term economic growth.

The report explores data connecting climate change with factors that contribute to society’s long-term resilience and prosperity—such as GDP growth, technology development, trade, jobs, reduced poverty, affordable energy, improved air quality and ecosystem health. This measurement framework aims to support evidence-based discussions about how Canada can address climate change while growing the economy and improving the wellbeing of Canadians.

Check out the full report here.

Peter WB Phillips is a member of the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices Expert Panel on Clean Growth and a contributor to the report.

Does your government really think your life is worth US$10 million?

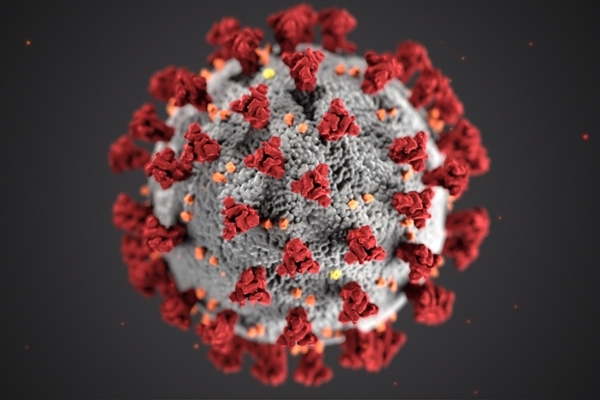

'The scale and severity of this disease is clearly much larger than recent pandemic outbreaks, but we now have enough knowledge to move to a more thoughtful, effective and efficient response to the pandemic.'

The current COVID-19 pandemic has generated an interesting conversation about how we should value human life. Many of the public health officials and politicians standing up and taking charge of the pandemic response assert that there is no limit to the value of any life—every life is worth saving, regardless of the cost. People are asserting every death avoided is worth up to US$10 million.

Do you really believe that that? I am an economist who studies risk management choices in Canada and abroad and I cannot help but conclude that this is baseless rhetoric that distorts our policy choices.

Let’s start with how you value your own life. At the most basic, you and I can buy insurance on our lives. The government offers a maximum $2,500 through CPP, so all workers have some coverage. We also can buy insurance though our employers, unions or from an insurance carrier. In 2016, 22 million Canadians had $4.3 trillion life insurance coverage, which works out at about $195,000 per insured person or $115,000 per average Canadian.

Economists think that measure vastly undervalues our lives. So they spend a lot of time trying to calculate the statistical value of your life. They do this by asking how much we might pay to avoid a specific risk or by watching how we make choices in our daily lives. Studies, for example, explore how much we each spend in time and resources to avoid risk, how much more compensation people need to do risky jobs or how much we will pay for safer cars. The numbers they derive vary widely across the developed world, from below $1M to almost $10M per life.

A more refined measure is the quality-adjusted life-year. Everyone will die sometime, so no specific measure actually saves a life, but rather we simply extend it by pushing back the date of death. Most of us are also interested in the quality of our lives, which each define in different ways depending on our personal circumstances. When economists attempt to measure this they get a wide range of results, from as little as a few thousand dollars for another year for those with painful or debilitating illnesses to hundreds of thousands of dollars for another year for otherwise healthy people.

Governments seldom agree with either our personal valuations or those offered by economists. In the simplest example, when governments and courts make payouts for wrongful death they seldom go so high, unless there was some wrongful error (aka tort). They like to keep these numbers secret but guesstimates are that they generally pay out more than $100K and less than $1M per person.

Another way to see what governments think you are worth is to look at the price they put on our lives in the rules they set. One easy example is in civil aviation, which is governed under an international agreement that sets the maximum payment for loss of life in an airline accident at about US$170,000.

We also can infer the government’s valuation of life by looking at the regulatory programs they implement. Governments regulate a wide range of products, processes, activities and spaces to reduce harms. How much governments will actually spend to avoid a premature death varies dramatically. I was shocked when I read a study that showed governments in North America and Europe were willing to spend extremely large amounts to save a human life from some risks (i.e. more than C$40 billion in today’s dollars for benzene emission controls in tire manufacturing plants) while in other circumstances even token amounts of investment are foregone (i.e. governments often are unwilling to spend less than C$1000 on screening for sickle cell anemia among new-born Africans and African-Americans for each death avoided).

The explanation for the difference between the high amounts we invest for little return and the trivial amounts we don’t invest for large returns is found in the nature of the risk itself. Voluntary, predictable and familiar risks — such as car accidents and heart attacks — often generate little public concern, which leads governments to under-invest in response. In contrast, involuntary, random and exotic risk — such as the prospect of being infected by new-variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease from BSE-infected cows or the new COVID-19 virus—generate outrage and panic, amplifying the perceived risk and leading to over-investment in assessing or managing that risk.

So where are we in that spectrum in our COVID-19 pandemic response? A recent draft study out of Yale University estimates that the world has spent (directly and through incurring the opportunity costs of isolation and work stoppage) in the range of US$22M to US$280M for each death avoided around the world, with an average cost of US$102M to prevent each death. Clearly we may be heavily tipped to the high end of costs.

We can also put that into Canadian terms. The Parliamentary Budget Office reports that so far the federal government has appropriated about C$145 billion to fight the disease and compensate people for lost jobs and income incurred in the pandemic response. The federal worst-case forecast for the disease was 44,000 deaths, and our current death toll is about 6,000. At that rate, each death avoided is costing almost $4 million. If we are really generous and assume 0.5% of all Canadians would ultimately die from COVID-19 without the policy (the latest global estimate of the infection fatality rate without public health measures), then we are still investing almost $800,000 per death avoided. That number is undoubtedly higher in reality as it does not count the outlays by other orders of government nor the uncompensated losses of workers, firms and investors.

Such a large response may be okay for the early stages of the pandemic as we face uncertainty about the severity of the illness and fears of overloading the healthcare system. But it is unsustainable over the longer term. We need to move away from this high cost model. Getting there requires new strategies to lower the cost by targeting measures to assist those most at risk. That will require all of us, experts and citizens alike, aggressively getting to know this disease better. Our scientists already know much that could assist us to manage our individual risk; we know how we catch it, what its symptoms and milestones are, when advanced treatment is needed and what risk of death we face.

The scale and severity of this disease is clearly much larger than recent pandemic outbreaks, but we now have enough knowledge to move to a more thoughtful, effective and efficient response to the pandemic. When I originally wrote this it suggested it may not be today, but soon; now I think soon has come.

Are we really at war with COVID-19?

The following blog post was originally published as part of the Canadian Science Policy Centre Editorial Series: Response to COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impacts. https://sciencepolicy.ca/response-covid-19

Our leaders and media have latched onto the war metaphor to describe the public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic. I don’t know about you, but I think that sends all the wrong signals and distorts the policy and public response we need.

In the recent past we have declared war on poverty, cancer, crime and disease, to name but a few. We launch these campaigns with great enthusiasm and a goal of vanquishing the enemy. Regrettably, outcomes seldom match the rhetorical goals and we often waste time and resources that could have made a difference.

The war metaphor imposes a set of assumptions that distorts how we think and act. In early days of the pandemic, the all-hands-on-deck strategy may have been the most effective way of responding.

But now we know more about the disease and have built medical capacity to assist those most in need. We now need to be exploring strategies to quickly yet safely restart our economic, social and community activities.

The war metaphor leads to a few simple yet wrong assumptions that will hurt this effort.

First, the war analogy implies there is some external aggressor. Initially that was foreigners, mostly coming from Wuhan or cruise ships, and now everyone from outside your neighbourhood. Barricades, police checks and information stop-checks between our provinces, at the boundaries of some communities, in cottage country and in many First Nations symbolize the idea that it is others that are infecting us. That is false logic now and undoubtedly distorts our actions.

Second, wars need to have a goal, and when context changes we should reassess our actions. Already in this pandemic circumstances have shifted widely, with little or no change in strategy. Our initial goal was to vanquish the disease, first by stopping its spread, then to flatten, plank and now, crush the curve. With more than 2 million confirmed cases worldwide (and up to 10 times more undiagnosed cases), COVID-19 is now endemic. We were going to have to find ways to live with it, rather than to vanquish it.

Third, wars tend to become all-in efforts. This creates all-in thinking and decision making. In the context of COVID-19, that has led to a total fixation on the infection and death rate of this single disease. For those in our hospitals, nothing else probably matters, but in a country of almost 38 million people, this war has engaged less than 20% of our population directly. The rest of us have been asked, some ordered, to cease activities and wait for instructions. In the meantime, everything else we value is in limbo. Jobs and retirement wealth are lost, firms are folding, other diseases are not being treated, and we are doing little or nothing to address other social priorities. The opportunity cost of the current strategy is high and growing.

Fourth, wars lead to unity of command. Governments everywhere are centralizing resources to fight the disease. This leads to overreach. The Liberal government in Ottawa sought unlimited spending and taxation powers without parliamentary oversight for 21 months and mooted invoking the Emergency Act to consolidate powers in the federal executive. Provinces, regions, cities and First Nations are arbitrarily setting up border checks, with no effective oversight. Cities have attempted to impose emergency orders beyond their competence to administer. Police are exploiting their new powers to enforce the letter of the law, regardless of the context and degree of risk involved. Most of these excesses have been pushed back but on-balance power is being centralized, with few benefits.

Finally, the one certainty of war is that truth is the first casualty. Governments in the heat of battle censor, distort and mislead to boost morale and create a unity of purpose. All governments in times of war distrust citizens and don’t have the time, patience or inclination to engage in normal debate. The cloak of war is well and truly in place in Canada, with most governments preferring to release only high level infection and death rates, to keep their underlying models and planning assumptions hidden and to generalize about the risks for the general population. We are only seeing what governments want us to see.

The military metaphor is especially poor as we begin to discuss the recovery and reconstruction effort that lies ahead. It is time to change the rhetoric.

Source URL: https://sciencepolicy.ca/news/are-we-really-war-covid-19

Artificial intelligence and decision-making

‘Artificial intelligence will only be an adjunct to decision making and not replace human decision making. It will allow for more timely and fulsome engagement with a myriad of data and will present it in ways that will influence decision makers.’

Photo credit: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Artificial intelligence (AI) presents an interesting set of opportunities and challenges for regulatory systems writ large. AI has a spectrum of possible outcomes. Some people think AI will become the computer that answers all the questions that could ever be asked or go beyond our ability as human beings to compute and choose. While that sounds like an interesting endgame, most of the people who are working on building the algorithms that underlie AI say that they are only going to be an adjunct to decision making and not replace human decision makers. AI will allow for more timely and fulsome engagement with a myriad of data and will present it in ways that will influence decision makers. So, firstly, AI is not going to replace human decision-making systems, especially regulatory systems; but it is going to be part of it. The question then is, what part will AI actually play?

Those who are excited by the prospects of machine learning assisting human decision making often assert that AI will speed things up and allow us to find nuances and connections that humans would only find after the fact. Getting to this point will require some engagement with both the inside of the algorithm and how the algorithms and their outputs actually get used by humans and human decision-making systems.

Inside the algorithms is an interesting space which is quite transparent at one level. Specialists say AI algorithms are pretty much open source. The things that do the steps that are required to compute the dynamic elements of a dataset are there, but the learning populations are not there and are not public. Algorithms are trained on real or artificial data, but that part is kept secret. So, everybody gets to use the tool, but it is human ingenuity that decides what the learning is anchored on and what reference points we will use. These are important to decision making because you can influence the outcomes of decision rubrics and tools depending on how you define the evidence that you are going to investigate. This part is currently proprietary and is a trade secret.

At the other end of the spectrum is the nature of the multiple iterative computations that have taken these tools and applied them to a learning population to draw inferences and advice out of them. This part is somewhat more transparent, but it is part of the whole system. There is a real question about auditing and accountability. Who decides what or how weights emerge is important because the machines may assign weights that may or may not reflect our preferences and our choices as society.

This is a big part of AI and just another extension of the debate about how evidence should influence public policy. Every piece of evidence at some point or another is subjective, regardless of how objectively we define, describe, measure, or use it. What we choose to make evidence is a preference.

The big challenge is to determine how algorithms can become transparent enough for the regulatory systems to see that they are not manipulating and distorting public interests and intentions. The flip side is that humans will not necessarily make the right choice just because a machine tells you what it thinks is the right answer. We have agency and the ability pick another option in spite of what the machine thinks or says. If anything, AI could tip us to the extremes of decision making, unless we are thoughtful about how we use the data.

AI is here to stay but like a lot of things, it is oversold and underdeveloped. It will eventually find its home in most human decision systems but will not replace the human being. Like any automated system, it reduces some of the mundane and problematic steps in decision systems and, if properly sited, should provide more autonomy for people to make better decisions with more information, rather than replace us in the decision grid.

Blockchain technology: Application and challenges

‘Blockchain has a real opportunity to contribute to more responsive quality assurance and this does not necessarily mean the best quality - it simply means you get whatever quality you want, with no gap between expectations and delivery.’

Application

Blockchain is the term everybody knows because a couple of Christmases ago we watched it spike over $20,000 a coin and then collapse a few days afterwards. In the financial world, it has the particular unique application of replacing the existing trust-based regulatory processes governing financial services through national money and banking systems. If we take one step back from the term blockchain, what we are really talking about are distributed ledger systems, which are really about trying to make as transparent as possible the nature of what everybody does in a value system, so that people cannot substitute or adulterate the system without transparently doing so.

In the context of a food system, we have lots of distance between the producer and the consumer (aka ‘food miles’), with frequent exchanges and transfers between independent parties who may work at cross purposes to each other and to the interests of the end consumer. Sometimes, we cross national boundaries that in a lot of cases have rapidly differentiating set of preferences and tolerances for how, where, when, who, and why a product is produced and distributed. In all of these cases, we have an existing trust-based supply chain based on a mix of very old style personal relationships that manage arm's-length and commercial contracts, with the heavy hand of the state saying “thou shalt” with punishments for those who do not obey.

Increasingly, we are using modern, flexible partnerships, alliances or relationships to assist. But each of those has the potential for inadvertent or deliberate substitution, adulteration or misrepresentation. In that context then, there is need to satisfy the increasingly intolerant or differentiated set of demands from consumers with the interests of those supplying them. National regulators, wholesalers, retailers, transportation companies, or seed companies each thinks they are assuring quality in a way that will generate value to the whole system. In this case, blockchain could offer new value because the distributed ledger will track all transfers and their terms and conditions. At one level, such an auditable system could reduce the potential for people to misrepresent by chance or by choice.

Blockchain has a real opportunity to contribute to more responsive quality assurance. This does not necessarily mean the best quality - it simply means you get whatever quality you want, with no gap between expectations and delivery. This could be a particularly powerful model but the challenge is that it needs to complement and engage with a very complicated and stylized space that uses a range of technologies that date back into the 18th and 19th centuries.

Challenges

The challenge for blockchain will be that the state will need to be part of the system because some of the things that need to be verified do not emerge by themselves. Sometimes, they are artifacts of the regulatory system, the science system or the ways companies and consumers define their wants, needs, preferences, standards and protocols, so there is still going to be a role for governance to define the elements that the blockchain will be tracking and tracing. Although the system is a backbone to transparency, what we make transparent and who cares, is beyond the system to define by itself.

Another challenge for blockchain distributed ledger applications is that sometimes there is a real disconnect, as different people see their information uniquely as their asset. A digital startup company or a seed company might say if they can just control this, then they can extract higher profits for their share of the supply chain. I do not think that system is going to work.

In some ways, the distributed ledger model is a bit like a public utility. In the context of other knowledge and information exchanges, the state was often a necessary partner in creating transparency and the rules that led to effective changes. Commodity markets, for instance, did not emerge by themselves and most of the commodity markets around the world experienced failures after they started because people discovered that there was asymmetric information. Stock exchanges or commodity markets now have rules about what has to be disclosed, when, how and to whom, so that everyone knows the last bid and ask price and the strike price in every contract. These kinds of rules will need to emerge in the blockchain world. They are already present in the context of the existing system but need to be translated to the new medium.

Would you know sound policy if you saw it?

The other day I was on a teleconference with a group of climate experts when someone asserted we were supposed to generate ‘sound policies’ to advance the climate agenda.

We read a brief description of soundness that stated such policies would be effective, efficient, equitable, focused and durable. We were directed to look for policies that would actually work at a minimal expense, distribute costs and benefits in some balanced way, avoid unintended impacts and last as long as needed to achieve the goals.

We quickly moved on, assuming that we all would know a sound policy if we saw one. As policy ‘wonks’ (know spelled backwards), we exuded confidence and conviction. That got me thinking – would our group (or any group) really be able to converge on a set of policies exhibiting those factors as ‘sound’? And if we did, would that list be legitimate?

This debate about sound policy is not new. Sometimes it is cast as a discussion about the role evidence can play in influencing or determining policy choices. Scholars, practitioners and citizens all have suggestions of policies they like – or more often policies they hate. I always ask the students in my first year graduate policy class to identify successes and failures. They are never short of ideas. The challenge is that the consensus advice from experts does not match our list. We want more or prefer different choices. That got me wondering how we might square this circle.

At one level, the definition of sound policy articulated for our teleconference conforms to the philosophical notion that a sound argument is both valid and has true premises, so that by definition the conclusion is true. For those of us who missed that course, I interpret this to mean that the assumptions are correct and the causal links are known, so that when a system is shocked, we get the predicted outcome.

So far so good. But is that enough for us to judge a policy as sound? In many ways we are asking about validity. Technocratic validation of the cause-and-effect relationships of a policy is vitally important—it is often called internal validity. We all should strive to avoid investing time and resources in things that simply have no hope of advancing our goals.

Is internal validity enough? It should be necessary, but if progress on a whole host of policy files, especially the environment and climate change, is anything to go by, it is far from sufficient. In many ways most of us refuse to defer to experts. We no longer want simply to be told what is best—we want to be convinced of the merit of their advice.

Climatologists and other scientists have, for the better part of two decades, been building the evidence to convince us that we need new policies to mitigate carbon release into the atmosphere. Economists and policy makers have proposed a range of policies to align the costs of carbon with those that generate them, in order to encourage individuals, companies and countries to lower carbon emissions. The experts assert the sound approach is to price carbon (in some way or another), to reduce countervailing subsidies (especially for oil and gas exploration and coal-fired power generation) and to incentivize mitigation, adaptation and innovation in industries and households. Most of the proposals are internally valid and have widespread expert support, but none seems to have convinced very many governments or citizens.

The problem is that few if any of these policies have been evaluated beyond the expert community. External validity is needed—we need to know that the advice underlying the candidate polices is both trustworthy and meaningful. In effect, we want to know whether the policies are applicable to the real world we live in.

Let’s go back to the five proposed criteria. While it is comforting to think that the five measures of internal soundness would help us to order and choose better polices, effective policies are not always the most efficient or equitable, and vice versa. So, we are inevitably forced to use our judgement on which variables are more important. Expert advice is inherently based on assumptions, beliefs, judgements and values. We want to know what they are. While experts say we should trust them, most of us are not convinced.

What is needed to externally validate a policy measure? That requires opening up the conversation about what is proposed, why and on what basis, disclosing all the assumptions, implicit and explicit value judgements and uncertainties.

- In the first instance, we need to see the full cause-and-effect story and the evidence in support of any measure, especially the diversity and range of responses to each application of the policy measures. Human and natural systems have significant variabilities. We need to know the most likely outcome, the range of possibilities, and the relative likelihood of them emerging.

- We need to see the assumptions that drive the analysis. What do the experts assume about what the economy looks like and how it operates? Is it competitive or concentrated? What do they assume about how people will respond to different incentives? Are people constrained in any important ways? What value do we put on the future benefits relative to impacts today (aka the discount rate)? Each of these assumptions can have a profound impact on whether a policy will actually work in the real world context and how one might rank them.

- Then we need to see the efficiency analysis. What costs and benefits are included? Which are excluded? What explicit or implicit value is put on different impacts at different times? The devil is always in the details.

- Next, we need to see the political economy analysis—we want to know the full array of expected winners and losers. Regulatory and policy systems are frequently captured and manipulated by those seeking to enrich themselves by writing the rules in their favour. As US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, “Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants.”

- Finally, we need some sense that those targeted by the policy will respond in the way intended. It is unreasonable to assume that people will do what policy makers want. In many jurisdictions, such as Canada, carbon taxes are combined with some form of credits or refunds to taxpayers, attempting to compensate them for their lost purchasing power. The underlying logic is that the change in relative prices should be enough to swing consumption away from carbon intensive activities. Is that true? Policies falter when they are so poorly designed that people can exploit their weaknesses or when the underlying goals and values are incommensurate or antagonistic to the targeted population.

Perhaps an example might put this into perspective. Right now, most governments that have grabbed hold of the climate agenda have adopted some form of pricing for carbon. While almost universally supported by experts as efficient, effective and equitable, the responses have ranged from nagging doubts to outright opposition in many places. The challenge is that while the case about carbon may have been made successfully, the pathway for impact between the taxes proposed and the emissions of carbon is vague—carbon is for the most part inferred using proxies so that the average consumer cannot conclusively see the relationship between the relative price changes they face and their emission of carbon. In some instances, especially where there are limited alternatives to existing production and consumption choices, the rising prices do nothing more than raise costs and marginally lower activity, making this a less efficient strategy than one that offers ready alternatives. Moreover, tax-based pricing tends to be regressive. Wealthier people may have the means to adapt to higher prices by retrofitting houses and buying electrical vehicles (often aided with further subsides); less well-off people simply become poorer. Finally, markets often work to shift the tax burden (aka the incidence); depending on the market structure, some taxes are borne where they are levied while other times taxes flow up or downstream in the supply chain.

Ultimately, we need to see a whole new set of information to validate the real-world applicability of any measure, especially those assumptions and value judgements about the trade-offs inherent in the policy. Only then can we advance towards sound policies that are enduring and able. Expert declarations are not enough; that lack of verifiable effectiveness, efficiency, equity and transparency threaten the durability of the policy.

The university innovation challenge

Canada relies on post-secondary researchers for far more of its research and development than most other OECD countries. Canada invests 0.66% of GDP through the higher education sector, compared with 0.42% in the OECD overall; the higher education sector undertakes more than 40% of Canada’s R&D compared with less than 18% in the rest of the OECD.

Given that, one wonders whether our university, hospital and polytechnic systems are up to the challenge.

Innovation can best be explored by drawing a metaphor from our biologist colleagues who assert that selective pressure, forced breeding and hybrid vigor are the basis for sustained and cumulative growth. Evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman, one of the complexity theorists from the Santé Fe Institute, stresses that the rate and scope of change in any system is a function of the number of adjacent potential opportunities.[1] The more that people and institutions are forced to interact with others, both from their own group and from beyond their group, the more likely the process of hybridization can work.

Some would assert that universities are particularly challenged in this context. Stephen Shapin, a historian of science from Harvard, reminds us that the academy is at root a medieval, monastic system that is about conservation and transmission of the stock of knowledge. In that context, our peer review, tenure and promotion, departmentalized structures and disciplinary communities have worked to refine and deepen our knowledge, but in an increasingly narrow and disconnected way. While we have made some effort to rewrite the rules and redesign the academy in the last 80 years, most of the underlying structures still encourage conformity and isolation.

Shapin asserts that today’s research university emerged from the German model developed in the 1890s, which was then translated around the world at the end of the Second World War. The success of the Manhattan Project elevated the status of scholars in the immediate post-war era. Governments, industry and NGOs, and citizens as a whole, now look to universities to engage in the exploration and resolution of real-world problems. In this way, we have opened the academy to a much greater mix of adjacent potentials, as most work on real-world problems draws on a diversity of theoretical approaches, uses a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods and both develops and analyses a wide array of different kinds of data and evidence.

Universities have taken up that challenge with new colleges and institutes, new interdisciplinary chairs, units and programs, and problem-based research teams. Each of these new interdisciplinary structures works to increase the adjacent potentials, initially within the divisions created by the natural scientists, social sciences and humanities, but increasingly between those divisions and beyond. Ultimately, universities are being challenged to build large scale capacity to address real-world problems—in Canada, most of the new granting money in the past two decades has been directed to that end.

Putting together teams with different worldviews and disciplinary backgrounds is both challenging and potentially rewarding. But the value we get depends on how we design the systems. A common hybridization is to put natural scientists together with social scientists and humanists. As scholars engaged in this effort, we tend to fall into one of four archetypes of collaboration:

First, we can follow the lead of sociologist Bruno Latour and do arms-length, fly-on-the-wall studies, using a mix of disinterested observation and external evaluation and validation through benchmarking, cost-benefit analysis and other organized project-level tools. In effect, scientists become the lab rats for other scholars.

Second, at times social scientists are included in science teams to ensure the process is responsible and reflexive. The Human Genome Project created this model and now ELSI, ELSA and GE3LS investigators (who study ethical, environmental, economic, legal and social aspects and impacts of new technology) are embedded in most large-scale science ventures to act as the conscience and moral compass for the scientific effort. In effect, social science research at worst is an ‘indulgence’ and at best a sagacious advisor.

Third, many science project leads are fully aware that their funders want to see measurable outcomes, in that their scientific advances are taken up and used in the market or society. In that context, social scientists often are enlisted as agents or contracted service providers to undertake studies that examine pathways to impact, assess freedom to operate, offer market analyses or advise on how to navigate the regulatory process. Many embedded GE3LS teams in Genome Canada projects end up doing this.

Fourth, probably the highest level of engagement involves social scientists acting as true research partners and collaborators, where they both undertake introspective assessments of the research agenda, discovery process and policy effects—including policy and research design, decision making, implementation and evaluation—and translate those findings to the management table of the larger scientific enterprise. A range of large-scale ventures aspire to that level. In Canada, we have supported a range of purposeful research ventures under the Networks of Centres of Excellence Program, SSHRC’s Partnership Grants, Genome Canada’s Large Scale Applied Research Project competitions and the Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

The key lesson to be drawn from all of our efforts to proactively amalgamate social and natural scientists is that design matters—a lot. Just putting different groups together does not necessarily create real actionable adjacent potentials. Changing how we see each other and engaging in real-time discourse and management is key to realizing new possibilities—and the foundation for creative discovery. Canada’s future may depend on how we realize this potential.

[1] Kauffman, Stuart (1995). At Home in the Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195111309.

It's time to change the climate debate

Climate policy in Canada, and in most other countries, has become trapped in an unproductive and distracting rhetorical debate. For some unfathomable reason, scientific and policy communities everywhere seem to believe they need to convince everyone of the merits of the scientific case underlying the need for policy action.

What people in the policy debate seem to be unwilling to recognize is that climate science has made a compelling and, more importantly for policy, an almost universally-accepted case that the accumulating emissions of carbon and other greenhouse gasses is either totally, or at least partially, the result of human action.

Climate change is now firmly fixed in the public consciousness. A recent YouGov survey of 30,000 people in 28 countries and regions revealed the vast majority of people — in every country surveyed —believe human action is partly or totally the cause of climate change.

The balance between those who see climate change as totally anthropomorphic (caused by humans) and those who see human activity as an important contributor to, but not the only source, varies across the countries surveyed. However, a strong majority believes climate change is here and it is a problem of our own making. In aggregate, the lowest level of support for human responsibility for climate change was 71% in Saudi Arabia and 75% in the US, with the highest support for human responsibility above 90% in more than half the countries surveyed.

Canada was not surveyed in the YouGov poll, but an EcoFiscal Commission commissioned a poll in 2018 that delivered consistent results. It showed 88% of Canadians agreed the climate is warming, with residents in every province overwhelmingly convinced. Similar to the US, only about 70% were convinced it was due to human activity. Every province reported a majority acknowledging human responsibility, with ranges from 82% in Quebec to 54% in Alberta.

In almost any other policy space, this level of agreement would provide overwhelming support for action. But the media and policy system seems to be fixated on the so-called climate-change deniers, who represent a vanishing small but often vocal portion of any population.

The Pew poll showed the US has the highest number of people, 9%, who accept the climate is changing but are unwilling to assign any blame to human development and only 6% who are true deniers that the climate is changing. To put this in context, a poll in 1997 reported about 16 million American adults were convinced Elvis Presley was alive—a full 20 years after his death. The poll found 6% of American adults agreed there was a possibility Elvis was still alive and 5% were unsure. Clearly some people will never accept certain things.

It’s time to move on to action. Changing the opinion of the few remaining skeptics is a fruitless exercise that distracts everyone from the task of actually acting. Proponents in few other policy fields feel the need to get universal acceptance of the underlying rationale for action. While it might be comforting to have everyone agree, it is far from necessary or feasible.

Few policy spaces could muster such strong support for action. Most other contentious policy spaces—including poverty, public health, tax reform, gun control, contraception, gender and end-of-life choices—have much higher rates of skepticism or denial and still have seen decisive policy action.

Moreover, people adapt regardless of what they believe. Most people, whether they conform with the majority or not, can find something they support or can participate in as we develop plans and actions to lower carbon emissions, build more resilient economies and communities and pursue green growth.

The continued effort of the many to convince the few of their errors is a waste of time and simply dissipates attention and energy. It’s time to move the debate to the options and strategies.

Sources:

https://ecofiscal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Ecosfiscal_Polling_February2018_FINAL_RELEASE.pdf

The significance of World Pulses Day

“Canada is well positioned to contribute in very important ways to global food security, and pulses are an increasingly important part of our contribution. We had the year of the pulses in 2017, so the world is beginning to recognize that what we produce is really important to feeding the world. Part of our job is to make sure we remember that too.”

Every food has some potential but some foods are better than others. The interesting thing is that, when one looks at an individual's diet, you definitely need protein, some fiber, and a lot of micronutrients that we are increasingly finding are important for body and brain function. And so we are learning what is required.

Generally, people who eat one or a narrow range of foodstuffs are more at risk of malnourishment than others. The good thing is that much of what we produce in Canada is actually strongly correlated with good nutrition. Our wheats have a broad range of amino acids, vitamins, and minerals that are critical for diets, far better than corn and rice, which have a much narrower range of micronutrients. Our pulses, similarly, have excellent protein, a good amount of fiber, and other materials, but also some micronutrients that are exactly what we need in our diet. Interestingly, canola is often forgotten as part of the diet. You need fat in your diet to be able to absorb many of these micronutrients, and canola oil is a very valuable part of our global oil consumption. At one level we produce grains and oil seeds that are bed rock to our global diet. If we used food pyramids, we would be at the bottom of the food pyramid and the foundation for all the rest. Fruits and vegetables are nice, but they are not the core of a diet.

Meanwhile, the higher order foods like animal proteins depend critically on the byproducts of pulses, wheat, canola and other crops, as the parts that we do not eat become feed for those animals which become part of our balanced diets in most parts of the world.

Canada is well positioned to contribute in very important ways to global food security, and pulses are an increasingly important part of our contribution. This was affirmed when the United Nations declared February 10 this year as the first world pulses day. We had the year of the pulses in 2017, so the world is beginning to recognize that what we produce is really important to feeding the world. Part of our job is to make sure we remember that too, because in many cases it is a business to us. We are producing a product that generates profit, but to many people this is the difference between an adequate diet that allows them to live whole lives or an inadequate diet that restricts their ability to contribute as producers or consumers in a society.

Implications for policy

These declaratory exercises where days and things are declared, are good signals. They help to remind the world and particular groups in the world, like the pulse producers and the pulse research community, that they are important. Sometimes, they can be influential in encouraging some of the marginal activity or some of the sustained activity that best analyses the research and the development that we do.

Food security and productive capacity

“It is clear that giving food to people may be a necessary short to medium-term part of the puzzle, because we owe it to the world not to let people die from the absolute absence of available food in their lives. But beyond that, the longer term solution is to try and assist these people, to acquire the capacity to become more productive.”

Food security is a fascinating problem space. Most of us think of food insecurity as people who are starving because of crop failures, or a complete absence of food. Undoubtedly, we do have people who are in that category; differentially, those people are isolated from other systems. They are not part of markets, and are beyond the effective reach of most states, so they cannot be helped and served by normal systems.

Interestingly, differentially, the people who are the most hungry are subsistence farmers in sub-Saharan African, Asia and parts of Latin America, where they literally cannot generate enough protein, micronutrients, and other nutritional attributes to survive. The challenge we have is to address that core group of very hungry, episodically catastrophically hungry, but generally malnourished people. It is a bit disturbing that in the last three years, the trend has been slightly up in terms of the absolute number of people who are hungry, as short term trends may be hints that there is a longer term problem out there. We have had a long-term decline in the number of people who are food insecure or hungry. As far back as 1820, ninety five percent of us were food insecure, and we were living on incomes of less than two dollars a day. And eighty five percent of us were absolutely insecure, in that we were living on less than a dollar a day.

So we have gone from a billion people to more than seven billion people, and we have taken the incidence of episodic and absolute malnourishment, from eighty five to ninety percent of our population, down to nine or ten percent. That does not mean the job is done, but that we have done a lot. Now the question is how do we deal with the last eight hundred or a million people who are differentially hungry?

Reducing hunger

The traditional strategies for reducing hunger were simply to give them food or make food available on some concessionary basis. In a worst case, food was dropped out of the back of an airplane as it flew overhead, where there were no roads. In better cases, food was actually delivered to the hungry people on the ground by aid workers. We are discovering that those strategies are not always that effective. They may deal with the immediate short-term problem which we have to obviously get over, but they often actually are counterproductive. These kinds of food solutions often end up causing longer term food insecurity, because you are dropping food into a food insecure part of the country, and depressing the prices and the value of any food that is left. There is never zero food; it is just scarce, and scarcity normally brings in new supply, which is usually priced higher and incentivizes people to produce, and deliver more food. But continually truncating this relationship means constantly isolating the hungriest, so that they are perpetually at risk of the environment and other conditions.

So what is the solution? There is no single strategy. It is clear that giving food to people may be a necessary short to medium-term part of the puzzle, because we owe it to the world not to let people die from the absolute absence of available food in their lives.

But beyond that, the longer term solution is to try and assist these people to acquire the capacity to become more productive. This usually means somehow extending the public and private infrastructure and markets into those communities, so that people can buy and sell inputs, buy and sell their own labor, or they can sell surpluses and buy during periods of shortages at the family level.

Very few countries are practically self-sufficient. We buy and sell food across our boundaries every day, because we want variety, or because we have to average out the shortages, and the peaks in our markets. States like Canada and some other large developed nations that have food surpluses, and are in areas which are resilient to climate change, are going to be increasingly important as other countries start buying and selling their foodstuffs.

Another part of it is that we need to maintain our productive capacity. Our farmers are both competing against other countries and in Canada for land, labor, and capital. This means that agriculture needs to remain vibrant, productive, and profitable. It usually also means good business practices, good capital practices, and good infrastructure, but, fundamentally productivity growth. The rest of the economy as a whole is adding one to two percent to its productivity, on an annualized basis over extended periods, and farming needs to do the same or its relative incomes or production will fall. This puts pressure on countries like Canada to direct some of its research and development efforts to sustaining our productive capacity and our exportable surpluses of foodstuffs. Canada is pretty big in the wheat, canola and pulse markets, which are the bedrock for the diets of many food insecure communities and families around the world.

Link to video: https://lnkd.in/e_Kk8-Y

Big data and risk assessment

“The big data world offers great opportunities for further driving out risks in our economies and societies, but it also runs the risk of swamping the system so that we get paralysis.”

Risk assessment is a system we constructed over the last generation of government and industry working together, to standardize and drive out risks from various activities we do. It involves a combination of risk assessment, risk management, and risk communication, and is all about probabilities and causal pathways. At one level, we do not need anything that is digital to make that system work. However, as the digital systems start to gather more data, different data, and faster data, it complicates and challenges our regulatory systems that are at the heart of these risk analysis enterprises.

It challenges them to figure out how to manage with the data flow, and bring meaning to data - data in and of itself is just noise, and sometimes, more information can just swamp a system, causing us to miss the critical variables. Sometimes, more information can deliver subtle little changes that allow us to find cause and effect relationships or impacts that we had not previously been able to detect. And so the challenge within regulatory systems is that they are fairly blunt instruments, which are created by governments, and populated by people who have standard training, and a lot of experience.

They are also very stylized places where we organize and manage our decisions. Having a sort of firehose of data flooding these systems, scares a lot of the regulators because they are uncertain how to deal with information or data that has no meaning attached to it.

The big data world offers great opportunities for further driving out risks in our economies and societies, but it also runs the risk of swamping the system so that we get paralysis.

Big data, risk assessment and consumer trust

The question here is whether the trust problem is a lack of real time credible data. At one level, more diverse, more timely, and more granular data, could be very useful for building trust with people. However, the big challenge will be the filtering process, when we are inundated with reams of data and multitudes of interpretations of that data. How does an average person make discrete choice of buying or not buying, or choosing between two products to buy or consume, because they need the products as part of their lifestyle and their livelihood? So there is this creative tension between more and better data helping to build confidence, trust, and better relationships between consumer interests and the production system, and the reality that people have scarce attention, and are not quite sure how to deal with information that they have not seen before and that comes from disparate sources and interests.

Governing in the digital age

“The digitizing of the world is changing what we can do and how we can do things. Theorists say a lot of the things we are now digitizing will, over time, move away from humans doing things to humans doing things aided by computers.”

The digitizing of the world is creating some interesting challenges. In the first instance, it is changing what we can do and how we can do things. There are some things that we were not able to do in the past, in terms of finding meaning and value in what groups of people do. This creates all kinds of business opportunities, some of which may be exploitive, or may actually hurt the people that have generated the data. It could be in the field of digital agriculture, or your online presence, as people figure out how to use your Amazon and Facebook posts to market more effectively to you. So there is a potential risk here.

The digitization of the world also changes what we can do. Theorists say a lot of the things we are now digitizing will, over time, move away from humans doing things to humans doing things aided by computers. In one endgame, humans may no longer be part of the creation process. This raises big questions about how we ensure that what emerges from those semi-autonomous and fully autonomous systems, are useful to us. This creates all kinds of governing challenges. Sometimes, the problem is that the action and the people that seem to own, control, and benefit from these new applications, are beyond our reach. For instance, WikiLeaks or Facebook problems and the potential interference in democratic processes by interested parties that are outside of any individual or electoral systems countries are all concerns for us.

There is the risk that some of these things just put the act of choice beyond any individual's or institution’s control. There are questions around how to set up rules and structures that govern semi-autonomous machinery, on our roads, in our hospitals, or in our research spaces. Digitization has created particular challenges for governments and non-government actors who govern part of the risk and returns in those spaces.

The flipside is that digitization changes how we can govern. Now, we have a lot more ability to connect to people and this, in theory, creates some opportunity for states and other actors, such as NGOs and corporations, to involve more people in decision-making. However, we are having trouble figuring out how to make this work. Involving more people does not necessarily lead to better decisions. This space is now ripe for research. Nobody has all the answers. I am not even sure anybody has all the questions, but it is an opportunity for scholars and practitioners to come together, and identify some things to work on jointly.

Implication of the pace of digitization on governance and policy

One of the challenges of digitization is that it moves at a whole variety of speeds, sometimes fast but also, sometimes very slow. For instance, in the area of digital agriculture where I work, there is a big impediment to actually getting the value people project out of their efforts. It takes a lot of time and energy to sample the soils, build datasets, and talk to each other, so that somebody can find some value. So at one level digitization is very slow.

At other levels, the creation of autonomous sensing and data manipulation is allowing things to happen in time scales that our formal governing systems could not comprehend. While some of it is very long and slow, and it's hard to see anything happening, another part of it is so quick that it complicates how we govern. Our earliest example of getting more digital was in the financial world, where flows of money sped up as we digitized the clearing and banking system. Now, we have around-the-clock trading in commodity markets, financial markets, and capital markets. On one hand, there are fewer random shocks in the system as systems tighten the margins, but at the other level, everything is integrated such that no one is isolated from the risks or problems in other part of the world spilling into our lives.